This dispatch is part of our Series: Hispanic Gen Z. This series is being crafted by a multidisciplinary team of RPA analysts, strategists, and behavioral scientists, including our Hispanic Inclusive Intelligence Team. The effort cites sources such as Census data, academic research, government studies, industry papers, and social media content.

In a survey conducted recently by the financial services company Empower, Gen Zers said that in order to be “financially successful,” they’d need an annual salary of $588K.1 $588K! That’s over 7x the real median income of households in the US (which includes all sources of income earned by all members of a household).2 And almost 18x the national average for entry level roles.3

In another recent survey, Americans overall estimated that about 20% of US households earn over $500K per year, while in reality these are “the one percent”.4 No doubt Gen Zers were especially likely to get this wrong—after all, they’ve spent thousands of hours consuming content from influencers like Mei Leung (“Let’s find out together what I spent in February … Clubbing: $86,070.33, Shopping: $33,274.72")5 and Conor McGregor (“I have two yachts … I was the first person to acquire the Lamborghini yacht … the Supercar of the Sea”).6 Tariffs or no tariffs, the “boom boom aesthetic” is sizzling-hot on social media.7 And with many Gen Zers spending more time there than IRL,8 it’s easy to feel left behind.

There’s a term for the disconnect: “money dysmorphia”.9 As financial expert Kara Pérez put it in a recent piece for The New York Times: “A lot of people are like, ‘I’m not Kim Kardashian, I’m not Elon Musk, therefore I am broke”.10

And if Gen Z overall is feeling the heat, the pressure is turned up even higher among Hispanic Gen Zers. Why? The TL; DR:

- Familismo Strikes Again: Many Hispanics feel the financial burden of past generational sacrifices; they don’t just need to earn for themselves, they also “owe it” to their families (past and current).

- Financial Baptism by Fire: Hispanic Gen Zers are also coming of age with less exposure to money-making pipelines than their Non-Hispanic peers, adding a layer of opacity to the wealth-building journey.

- El Sueño Americano: The American Dream, meanwhile, still looms large, with many Hispanic families enthusiastically pushing their Gen Z children towards the golden triad of college, career, and home-buying—even when the TikTok Generation might have other priorities in mind.

1

Familismo Strikes Again

In Hispanic culture, “la familia es todo.” Taking care of the family, and including the family in major life decisions, is both a shared value and a cultural imperative.11 Familismo has countless benefits, among them a profound stress-buffering effect.12 But as discussed in Dispatch #2, for many Hispanic Gen Zers familismo also creates unique challenges.

The majority of Hispanic Gen Zers are US-born children of immigrants.And they are acutely aware of sacrifices their parents and grandparents have made.13 As writer Diana Morales puts it, an attendant “first-generational guilt” can set in early in life: “Being raised by a Mexican single mother I was constantly reminded that she moved to the United States for a better brighter future for her and her kids…I have a specific memory from when I was younger learning about dinosaurs and coming home from school excited to tell my mom. She didn’t know much about dinosaurs to my confusion… Later my 2 older sisters talked with me that she didn’t get to learn that in school because of hardships she had in Mexico. Guilt took over.”14

Reporting on the pressure that Hispanics feel to start taking care of their families, even at an early age, writer Janel Martinez shares the story of Giselle González: “At 15 years old, the eldest daughter of Mexican immigrants taught herself to do acrylic nails, charging friends and associates to do their manicures, and would use her earnings to assist with groceries, the phone bill, or transportation. If her younger brother needed something, like lunch money, González would step in to support”.15 The emotional backdrop here is deeply nuanced. In addition to feelings of indebtedness and duty, there is also resentment (at having adult-sized responsibilities), guilt (for feeling resentment), and shame (for out-learning and out-earning one’s parents)—as well as gratitude (for parents’ sacrifices), pride (for being able to repay the sacrifices), and intense love and closeness. It’s complicated.

Many children of immigrants can relate, not just Hispanics. Psychologist Emily Soukhanouvong, a child of immigrant parents from Laos, says that first-gen guilt is widespread: “The expectation to excel academically, professionally, and socially while honoring cultural traditions and familial obligations can feel overwhelming...If you grew up in an immigrant household, it’s not uncommon to ‘feel bad’ (aka guilty) about yourself when experiencing sadness, frustration or anger when thinking about the sacrifices your family made for a better life.”16

One thing that’s unique to Hispanics, though, is that there is often significant financial need. Compared to their Non-Hispanic counterparts, Hispanic Gen Zers come from households that are economically constrained.17 And it is not uncommon to carry heavy financial burdens. For example, McKinsey & Company has reported that one-third of Hispanics send remittances to family outside the US, and that more than two-thirds of said families are sending up to 30% of their income abroad.18 Moreover, Hispanic Gen Zers’ parents have often not had the types of careers that would afford them livable savings accounts or retirement plans.19 So many Hispanic children feel responsible to help.

Also unique to Hispanics is the fact that financial obligations can feel limitless. As content creator Saul V. Gomez explains on the podcast Todo Chido: “I want to give all my money away to like my family just so I don’t feel guilty. I don’t think I’ll feel like I made it until like my parents and my brother don’t work.”20 His co-host then concurs, and adds to the list: More siblings, nephews, and not just current children but also future children. On TikTok, meanwhile, it’s common for Hispanic creators to broadcast “retiring their parents” and funding multigenerational vacations. It’s no wonder Hispanic Gen Zers feel financially under water. Unlike their Non-Hispanic counterparts, who just need to be as rich as Kylie Jenner or MrBeast, Hispanic Gen Zers carry the added psychological burden of thinking about a whole network of family members.

And among Hispanic Gen Zers as a group, providing for family is a normative goal. Something that isn’t the case among all first-gen groups. Research from Bank of America shows that family is a significantly bigger financial motivator for Hispanic Gen Zers than it is for Gen Zers overall. In a similar vein, well over half (57%) of Hispanic Gen Zers say that being able to provide for their family’s future is part of their definition of financial success.21 The same study found that almost three-quarters (72%) of Hispanic Millennials were currently providing financial support to family.22 Again, for Hispanic Gen Z success isn’t just about being as rich as the one-percent; it’s bringing your whole family along too.

Without a doubt, the financial burden on Hispanic Gen Zers is not just psychological but also literal. As Saul V. Gomez, talking on another podcast, points out: “It’s harder for Latinos to ‘make it out’ or save money, because they spend a lot of money on each other…You’re worried about paying everybody else’s bills and making sure everybody else is fine, and that’s why like we just get stuck in a position.”23

Video Credit: @buenobuenopod on TikTok, featuring Saul V. Gomez

TurboTax campaign “Nunca Es Solo Un Reembolso"

2

Financial Baptism by Fire

A second challenge faced by Hispanic Gen Zers—in addition to the complexities surrounding familismo—is limited familiarity with money-making pipelines. Compared to their Non-Hispanic peers, many Hispanic Gen Zers are coming of age with only a rudimentary understanding of credit-building, stock market investing, and retirement planning. More often than not, their parents and other relatives are emotionally supportive but less-than-100% effective when it comes to reliably guiding them through processes like applying for student aid or taking out a home mortgage. As reported recently by The Harris Poll, just over half (54%) of Hispanics overall consider themselves financially literate, compared to 69% of Non-Hispanics.25 For many Hispanic Gen Zers, navigating financial systems and instruments is therefore a kind of baptism by fire.

Part of the reason for this relates to immigration status: Hispanic parents may know the Chilean or Dominican financial system backwards and upside down, but immigrants as a whole tend, understandably, to be less well-versed in the workings of the US system, and less trusting of it.26 A second part is that Hispanics have less familial wealth, and less generational wealth in particular.27 In families where wealth is a birthright, knowledge about money—like the money itself—just flows more freely.

Despite a strong emphasis on familial support, most Hispanic Gen Zers (65%) say their parents didn’t talk about finances openly while they were growing up.28 And some Hispanic households even consider money-talk to be taboo.26 Moreover, nearly half (48%) of Hispanic Gen Z say they were never offered financial education in school, compared to 37% of their Non-Hispanic peers.29

Taking all these stats together, it’s not surprising that Hispanic Gen Zers are more likely than their Non-Hispanic peers to say they don’t have any investments because they simply “do not know where to start” (42% vs. 27%).28

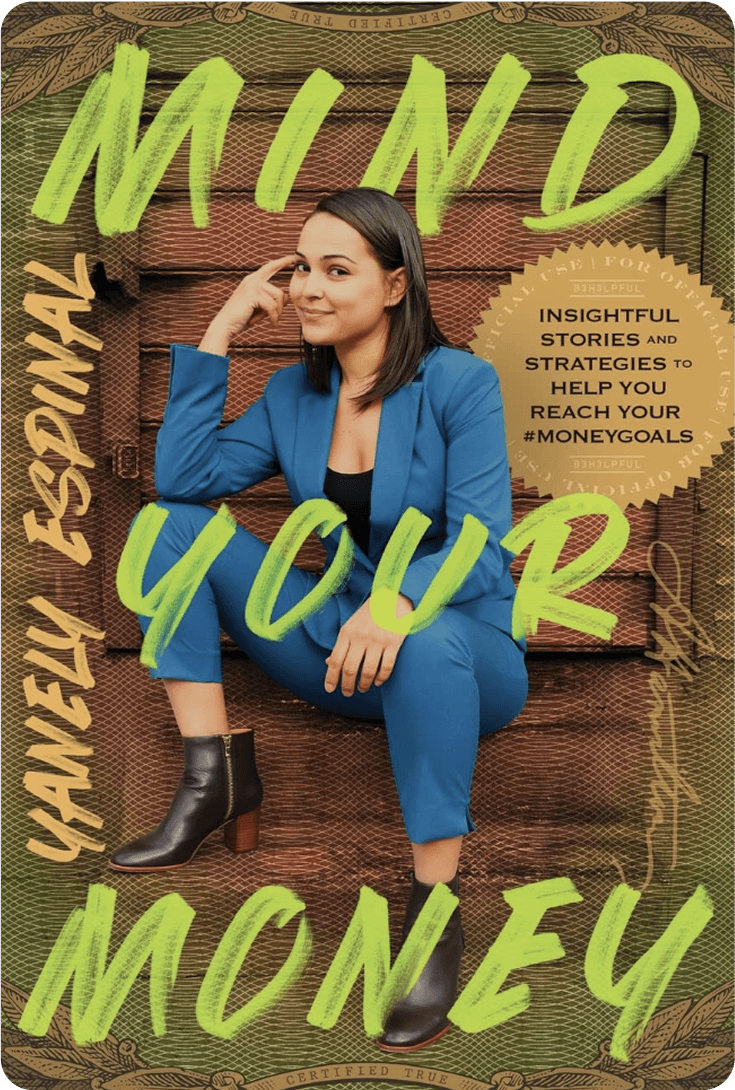

It should be mentioned that “soft financial decisions” are affected too. Financial educator and author Yanely Espinal frequently shares social posts about how Hispanic culture subtly encourages people to help friends and family in need—for example by helping with expenses or co-signing loans—even when they aren’t in a position to do so.30 And, as Redditor @PPP1737 on r/LatinoPeopleTwitter writes: “My mom didn’t go to school past 5th grade. My grandmother never learned to read. I had zero help or guidance from family on how to pick out and apply to colleges much less direction on how to pick a major. No help navigating the required courses or getting internships to be successful in a field."31 All of this means, of course, a steeper financial hill to climb.

LinkedIn post promoting Wells Fargo’s collaboration with East Harlem chefs, “Sabor y Sabiduría”

3

El Sueño Americano

Swirling around all of the issues mentioned above is the ever-present glitter of el sueño americano, or the American Dream. Yes, Americans overall say their faith in the American Dream has dimmed in recent years given the rising cost of living.35 And yes, younger generations have begun to reimagine the American Dream in terms of lifestyle achievements vs. purely financial ones.36 But in Hispanic families, belief in the original version of el sueño americano has historically held strong.37 While recent changes to border and immigration policy have no doubt cast a heavy shadow, hope for the American Dream persists.

In part this hope has to do with the immigrant frame. As Wellington Moreno, a naturalized U.S. citizen who was born in the Dominican Republic, puts it, “I have a certain perspective on what really poor actually is, and how high you can go…Here, the sky is the limit. The sky is not even the limit.”35 In part, too, this hope has to do with a core alignment between the Hispanic value of hard work and the meritocratic ideals that underpin the American Dream. It also seems reasonable to infer a certain level of psychological necessity: Hispanic families have often made enormous sacrifices to pursue life in the states; abandoning faith in el sueño may feel unimaginable.

For Hispanic Gen Zers, then, the vast majority of whom have immigrant parents or relatives,38 there are great expectations. Hispanic parents often enthusiastically push their Gen Z children towards college, career, and home-buying—three significant milestones that may have eluded them personally—even when the children themselves may have somewhat different aspirations in mind.

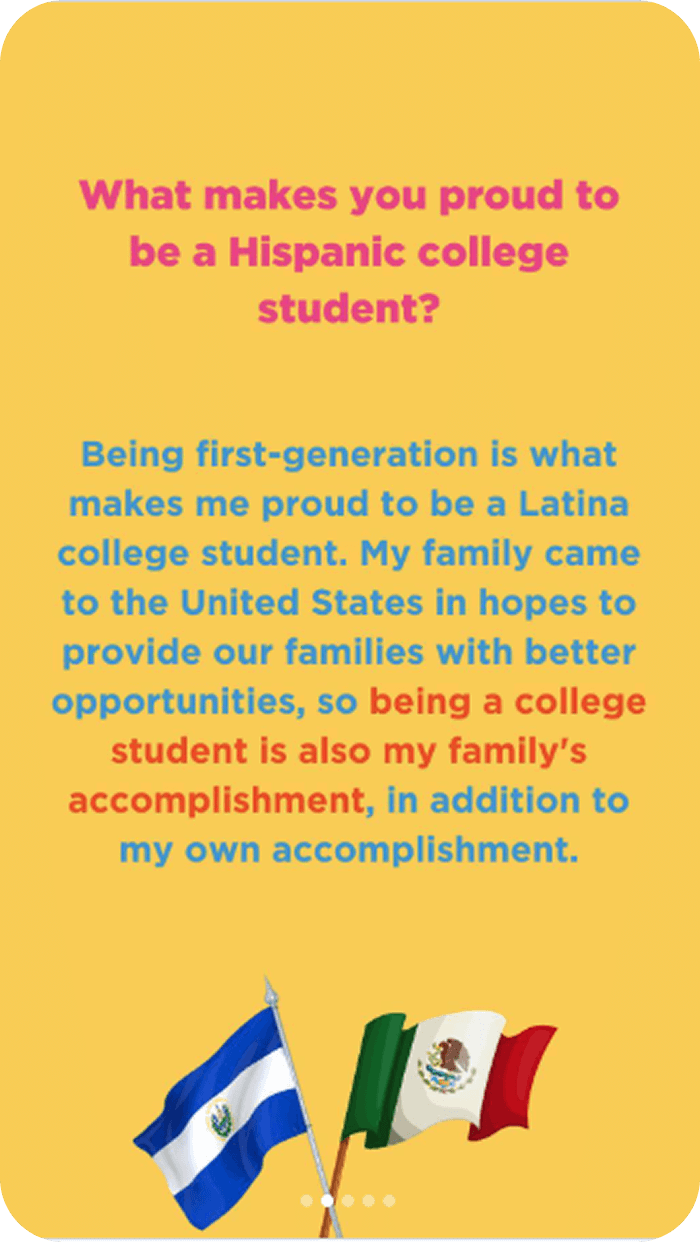

First, there’s college. Compared to other groups in the US, Hispanics have tended to see education as the path towards upward mobility, and a non-negotiable for families who can afford it.37 Hispanics have in turn seen enormous gains in enrollment at four-year institutions (a 287% increase, in fact, between 2000 and 2020).39 Gains that have been fueled by rock-solid dedication and hard work. Indeed, a familiar refrain in many Hispanic households is “ponte laspiles” (“put in your batteries,” or “buckle up and get to work”). Given the context of familismo, performance in school is understood by all to reflect back on the family. And of course this raises the stakes. As one first-generation college student put it, “I felt like a lot of pressure, because they put, like, so much pressure into me being okay and me having all the resources that I need. Yes it is for myself, but it’s also, like, to repay them.”40

@beyondtwelve on Instagram, discussing college as a family accomplishment

Despite the positive emphasis on education, Hispanic parents can seem myopically focused on getting a college degree to the exclusion of quality of experience. The same first-generation student mentioned above tells us, “my dad was like, okay, college in general, it doesn’t really matter where, just go.” In a similar vein, high school senior Karen Carreño, in a video for PBS News Student Reporting Labs, says, “a lot of Hispanic parents pressure their kids to stay close because they have a stronger value of family,” even when that means bypassing top-choice schools.41 A third student, talking about her parents’ insistence that she live at home during her college years, says, “I kind of felt like I wasn’t getting that college experience. Right after high school I just felt like I was like stuck at home, like I was still in high school.”41 Art school, gap years, and other nontraditional paths may also be eschewed by Hispanic parents outright, without careful consideration of their merits. Meanwhile Hispanic families’ laser focus on getting a college degree can make Hispanic students disproportionately vulnerable to entanglements with for-profit institutions.42

For Hispanic Gen Zers who are already feeling the pressures of society at large—the pressures to make money and carve out a successful career, stat—parents’ educational dreams for them can feel like an inherited, sometimes-off-base, mandate: Rooted in best intentions, but leaving little space for self-direction.

Next come career, homeownership (and of course bringing family along). The sueño script continues. And much could be written about familial expectations in all of these areas. But when it comes to Hispanic Gen Zers’ relationship to money, a few points merit most attention:

- Hispanic Gen Zers who pursue corporate careers often feel these jobs are misunderstood, even underappreciated, by their families. As TikToker @nrmdls explains in a video that garnered over 3 million views, “they kind of just assume that I don’t work because I’m not doing backbreaking labor.” He adds, “I don’t use my corporate personality outside of work because my family will scold me…they’ll call me White.” He then goes on to defend slacks and dress shirts.43 Other Hispanic Gen Zers mention getting low-key shamed for having “soft hands.” Gen Zers from all cultures sometimes say their parents don’t understand what they do. But this is a recurrent theme among Hispanics, and the experience can be heavily laced with guilt given the more physically challenging jobs that other family members may have. When it comes to pursuing a money-making career, then, there is at once a cultural push-towards and a cultural pull-away-from.

- Aspirations for el sueño americano notwithstanding, Hispanic Gen Zers and their families alike typically reject the notion of the “self-made” individual. As Yanely Espinal writes, “‘Self-made’ is a term that allows us to completely disregard the importance of gratitude once we succeed. Yes - I work hard AF, but there are MANY people who played a role in me having the life thatI have today!!!”44 Even if Hispanic Gen Zers step into college and corporate experiences that their families and communities don’t quite understand, there is always a sense that individual accomplishments are collectively earned.

- If college is the opening chapter of el sueño americano, home ownership is the final act. Many Hispanic families see renting as throwing money away, and buying a home as the ultimate financial accomplishment. After all, the home is often viewed as a multigenerational asset, providing a sense of pride, place, and security for the entire family (what IRA account does that?). This cultural focus on home ownership is powerful. On TikTok, scores of Hispanic Gen Zers showcase first homes that feature bedrooms and other spaces specifically designated for parents and other family members. These are super-happy videos full of celebration. There is a palpable exuberance in having made it against the odds; in “going big;” and in sharing the spoils with family.

- At the same time, the focus on homeownership can be stressful too. Hispanic Gen Zers sometimes rush into home buying too early. As a result, some may overspend; some may take on less-than-optimal financing;45 and some may forego personal savings. Those who wait, meanwhile, can feel bad for waiting. And those who just don’t earn enough to buy a home can feel “broke,”even if they’re not broke at all. In short, homeownership carries huge excitement and symbolic value for many Hispanic Gen Zers. But the pressure sometimes adds stress on financial planning.

Quickbooks campaign “Turning -Ito into -Ote,” featuring Javier “Chicharito” Hernández

Conclusion

A 2024 Qualtrics study found that nearly a third of all Americans feel money dysmorphia, including 43% of Gen Z. Meanwhile 27% of Americans say they are “obsessed with the idea of being rich,” and 44% of Gen Z admitted to “rich obsession”.49 Oh, and the Empower study mentioned at the top of this article? It found that Gen Z would also need a net worth of $10.5M to feel “financially successful.” On top of the $588K/year salary.

For Gen Z overall, making money is a crazy-daunting operation. For Hispanic Gen Zers there is a thick soup of added complexity: Navigating financial systems with minimal familial guidance; feeling at once honored to “repay” family and frustrated at being “the family ATM;” and facing the pressure and pride of becoming a living model of el sueño americano. Marketing that acknowledge this complexity in a relatable, culturally-aware way will resonate with Hispanic Gen Zers. Marketing that gives Hispanic Gen Zers a chance to breathe, provides them with the opportunities to explore a wider range of options, or equips them tools to make things easier, will resonate even more.

In this Series:

Dispatch #1: Who are "Gen Z Hispanics?"

Dispatch #2: "The Hardest Thing I've Ever Done"

Dispatch #4: You Know You're Hispanic When...

Note: In this report, we are looking to uncover overarching patterns. So, we will often make general observations and predictions. We recognize that we may overlook individual, subgroup, and intersectional differences in doing this, but our project is trained on broad trends. More micro trends will be important for marketers to dive into on a case-by-case basis. We also recognize that the statistics and content available to us as third-party researchers may be biased, incomplete, or otherwise flawed. To address this, we’ve sought to source information in various forms, from various places, and to gut-check and fact-check wherever possible. But the information we are working with isn’t always perfect. Finally, we are also using the term “Hispanic” loosely, often interchangeably with the terms “Latino” and “Latine,” to refer to groups with Spanish-speaking heritage. “Hispanic” is the term that is largely preferred based on current research, though we recognize that different terms differ in meaning and nuance.

Sources: